In Cell Structural Biology

In situ Cryo-EM

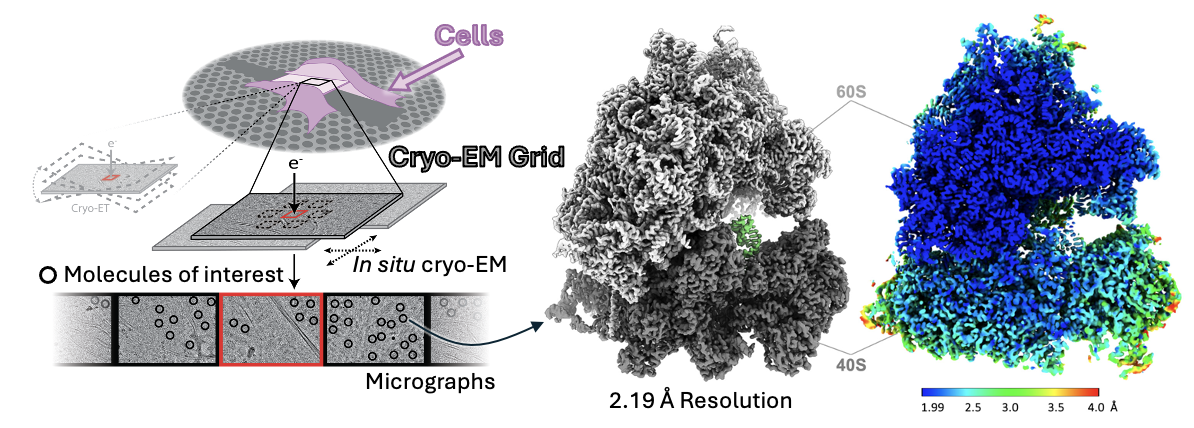

Scientists have long been interested in studying the detailed structures of large biological molecules in their natural environments within cells. However, traditional cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) requires very thin samples for electrons to pass through and create an image, and most cells are too thick for this method to work directly. Recently, advances in technology have made it possible to cut individual cells into extremely thin slices (about 100 nm thick) while keeping them frozen, using a tool called a focused ion beam (FIB). Initially, this method was combined with cryogenic electron tomography (cryo-ET) to capture the 3D images of these slices. However, the resolution was limited because the process of collecting data was slow, resulting in only small amounts of data.

Instead of using cryo-ET, our lab has pioneered a new approach that combines FIB-milling with single-particle cryo-EM. This method is faster and potentially allows higher resolution 3D reconstruction. Using this method, we visualized human ribosomes directly inside HEK293T cells, gaining insights into how ribosomes work during protein synthesis and what ligands they natively bind to in the cells.

Instead of using cryo-ET, our lab has pioneered a new approach that combines FIB-milling with single-particle cryo-EM. This method is faster and potentially allows higher resolution 3D reconstruction. Using this method, we visualized human ribosomes directly inside HEK293T cells, gaining insights into how ribosomes work during protein synthesis and what ligands they natively bind to in the cells.Native Ribosomes at High Resolutions

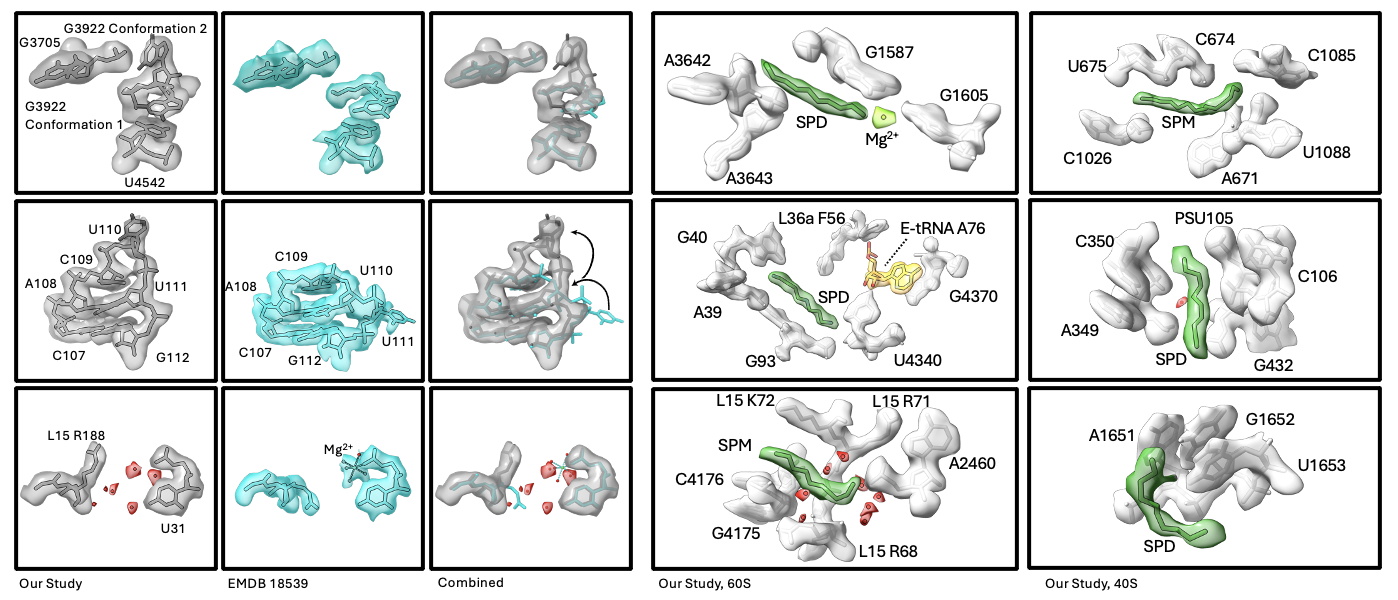

Why is it important to study biological molecules like ribosomes in situ? The answer lies in the differences we observe between ribosomes from our in situ studies and those previously published from in vitro datasets. On a small scale, we observed different rRNA conformations in several locations, and many cases where ion and small molecule binding are different. Previously, the presence of ion and ligands were often dependent on the buffer being used. For the first time, we were able to observe the native ligand and ion environment in human ribosomes. Surprisingly, we identified 21 polyamines (spermine or SPM, spermidine or SPD, putrescine or PUT) bound to the ribosome. Several examples are shown below.

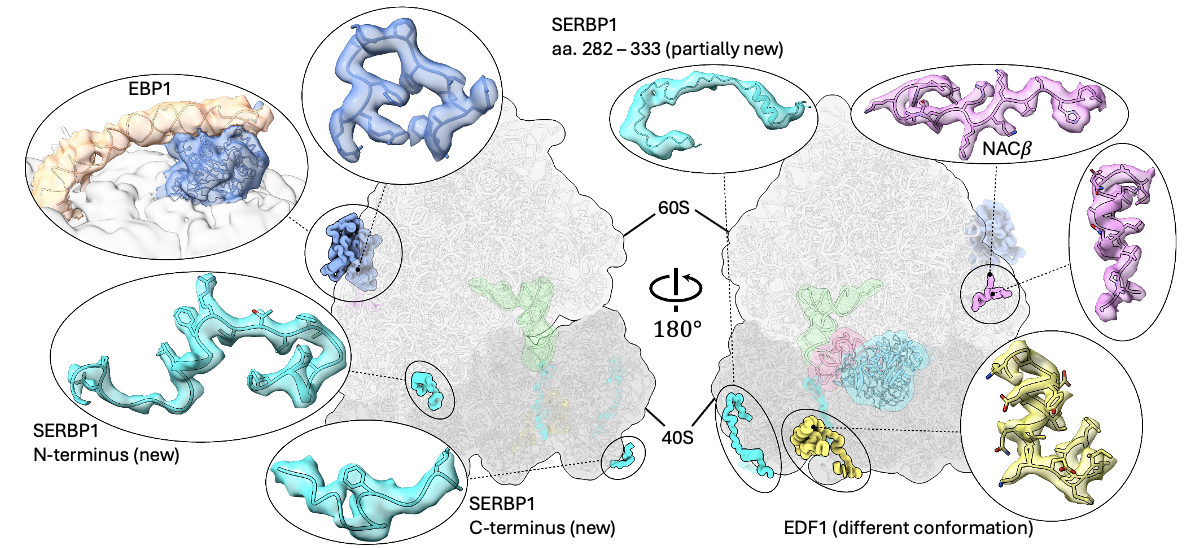

On a larger scale, we observed various additional proteins bound to the ribosome. Some of them have never been captured before, and some others are captured in different conformations. For densities that were never resolved before, we managed to “sequence” them through the shape of their density (i.e., “sequencing” through cryo-EM) and confirm our result with state-of-the-art AlphaFold prediction.

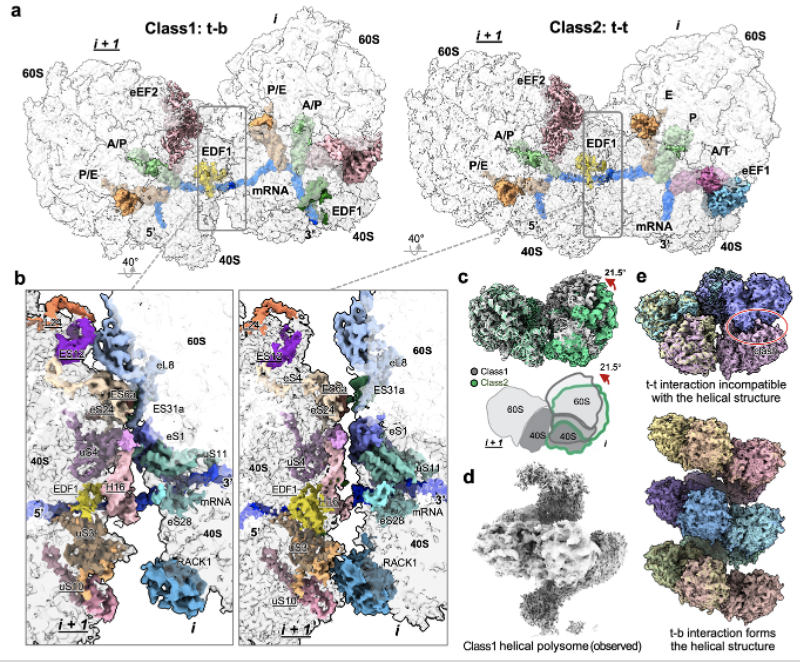

Unlike purified ribosomes, most ribosomes in cells are engaged in active translation. When multiple ribosomes work on the same molecule of mRNA transcript, they sometimes collide into each other and form large structures called polysomes. From our in situ dataset, we captured two main types of polysomes in high resolution, revealing how ribosomes interact when they collide. Interestingly, one type of polysome (class 1) can form larger scale helical polysomes consisting of more than 4 ribosomes. The distinct polysome interfaces might explain how cells distinguish between small collisions that can resolve themselves (class 2) and larger, more serious collisions (class 1) that require special translation rescue factors to resolve.

Native Elongation Dynamics

Translation elongation is a dynamic and complex process where ribosomes add amino acids to a growing protein chain. This involves a lot of coordinated movements, including ribosome small subunit rotation, the binding and dissociation of elongation factors, and the movement of tRNA and mRNA. By using 3D classification, we were able to capture ribosomes in different stages of this process. Surprisingly, we found many ribosomes have tRNA in the recently discovered Z-site. In previous studies, Z-site was often associated with ribosome hibernation. Our study suggests that Z-site could be involved in active translation as well.

Everything Everywhere All at Once!

A key feature of in situ data is that raw datasets contain the full repertoire of cellular factors and can be reanalyzed for entirely different macromolecular targets. This versatility opens exciting possibilities for structural biology to uncover the mechanisms of various cellular processes as they occur in their native context and to study differences across cell types or even among patient samples. We welcome passionate researchers to join our lab to help uncover the molecular mechanism of other cellular processes in the native cellular environment.